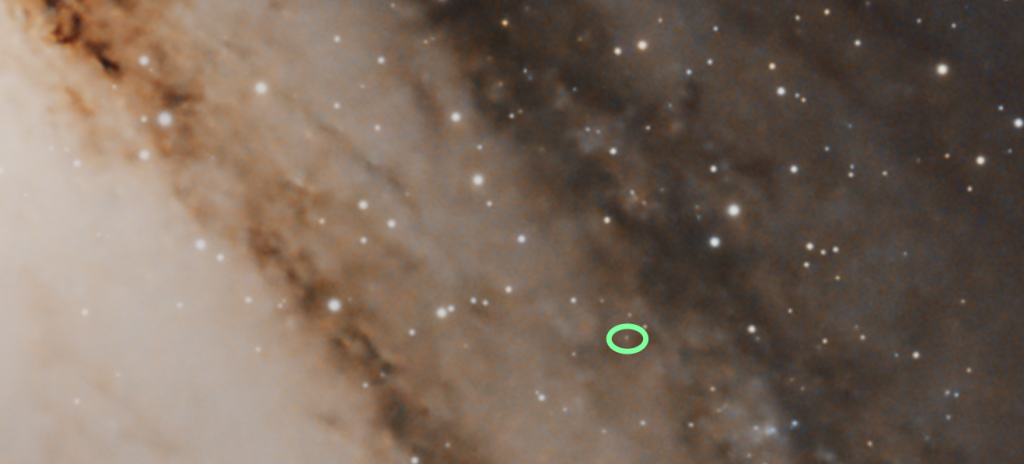

Andromeda widefield

I’ve been considering a widefield scope for a long while and looked at countless reviews from different manufacturers. In the end I decided to just get the new Askar SQA55 without even reading a single review based on its technical parameters.

It arrived yesterday and somewhat surprisingly came with clear skies. Here’s my first light with it, about 6.5 hours on the Andromeda Galaxy.

The difference with setting up a newtonian is unsettling at first. There’s no backspace to consider, no collimation and balancing is not really a thing with a small scope like this. And while the result is a nice crisp image, I do think it can’t replace the deep field of a newt.

But I did manage to find a special star in my image. Here is M31-V0619, the original Cepheid Variable that Hubble discovered and measured so he could conclude M31 being a galaxy on its own and not some nebula in our own Milky Way.